.jpg)

Scott never wrote about the Vedute that hung in his Edinburgh dining room (unlike Eisenstein, he had not bartered with a provincial Russian museum to secure them, having taken the easier route of inheriting from an uncle), but the prints’ dramatic entanglements of heroic history, ruination, and busy human actors surely reverberated with the author of Ivanhoe. When Eisenstein wrote, “I am now looking at this etching on my wall,” it was 1946, and he was in his Moscow apartment with eyes on Carcere oscura ( Dark Prison). Sergei Eisenstein, Sir Walter Scott, and my late in-laws had little in common but for the chosen companionship of Piranesi. Louis Kahn, champion of modernist monumentality, had Piranesi’s quixotic plan of the Campo Marzio in his Philadelphia office Peter Eisenman, architecture’s field marshal of fragmentation, has the same print in his bedroom.

Jorge Luis Borges and Le Corbusier were aesthetic and philosophical adversaries, but both decorated their rooms with Vedute (the overgrown Remains of the Temple of the God Canopus for Borges, the cubic block of the View of the Villa Albani for Corbu). His prints pop up like background chatter in photographs, fictions, and Logan Roy’s living room in Succession’s fourth season. Look around, though, and somehow poor Piranesi is still everywhere.

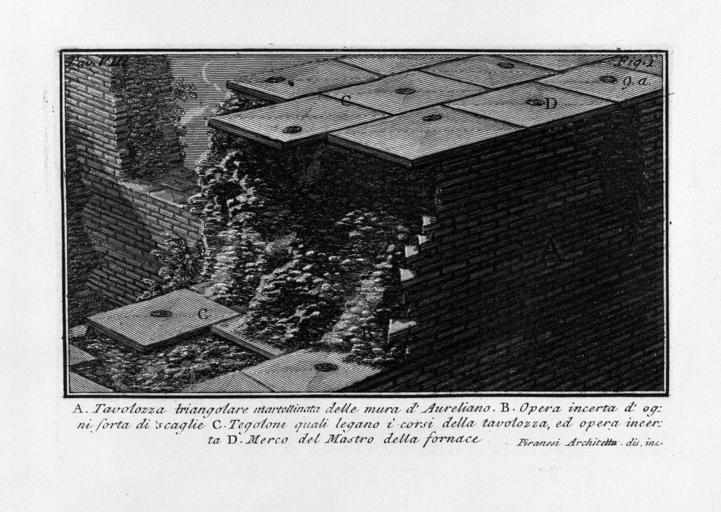

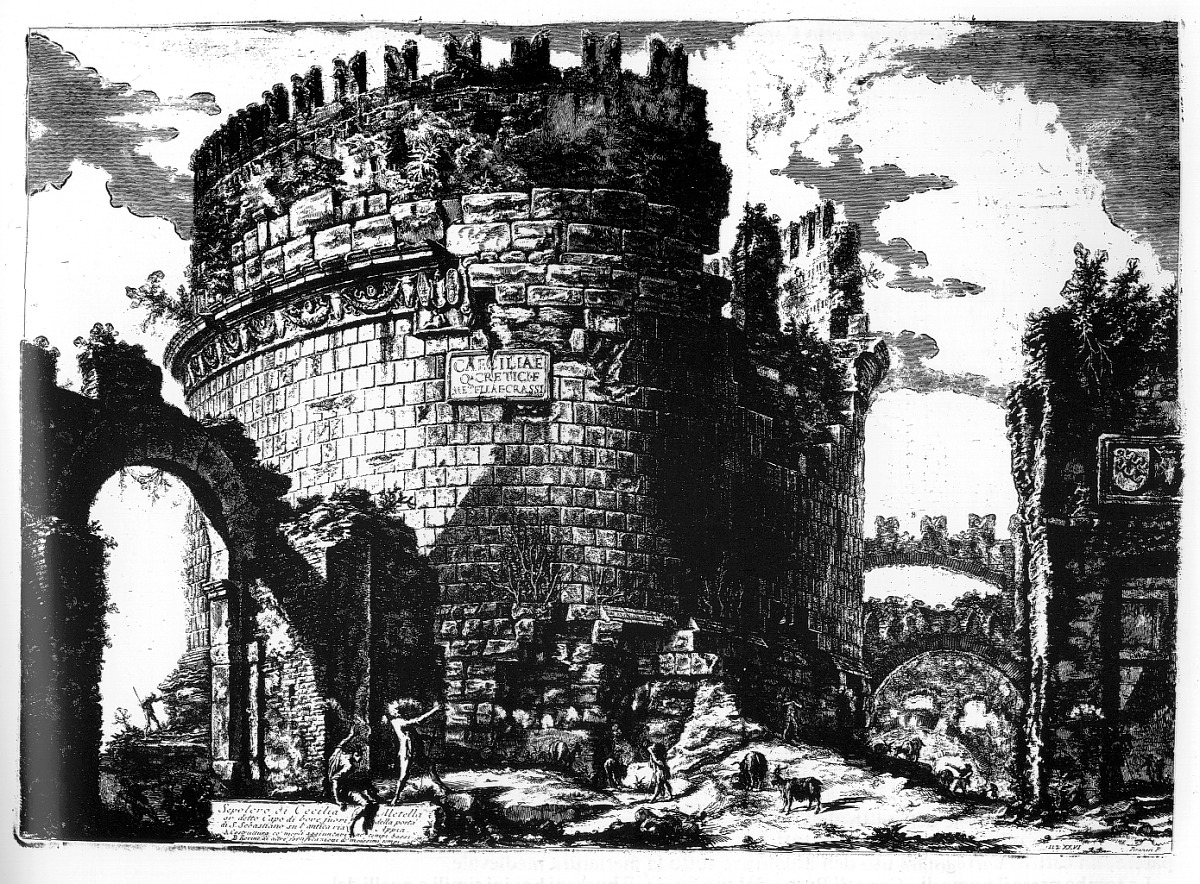

The American Joseph Pennell, a leading light of the nineteenth-century etching revival, acknowledged his existence only to observe, “His perspective is as poor as his industry is great.” In Prints and Visual Communication (1953), one of the twentieth century’s most influential texts on printed images, William Ivins (the founding curator of the Metropolitan Museum’s Department of Prints) described him as “a commercial manufacturer of architectural prints-conveyors of information- rarely let his genius interfere with his business.” The definitive twenty-one-volume roster of important print artists, Adam Bartsch’s Le Peintre-Graveur (1803–1821), ignored him. Preceding the dark vaults and pointless bridges of the Carceri were the first of the Vedute di Roma ( Views of Rome, 1745–1778) that were sold in volume to travelers on the Grand Tour and defined the popular image of Rome for generations: the theatrical slanting light, the grandiosity, the squalor.īut just as the architectural establishment, bewildered by Piranesi’s effervescent schemes, treated him as a crank (the architect Luigi Vanvitelli called him a “lunatic”), print connoisseurs, put off in part by his entrepreneurial success, dismissed him as a hack. His prints, in the meantime, made him famous. When he took up printmaking, it was to make ends meet, and his elaborate title pages announced the authorship of “Giambattista Piranesi, Venetian Architect,” but he died with just one significant architectural project to his name. The actual Piranesi was born in the Veneto in 1720 and went to Rome at the age of nineteen with the dream of becoming an architect. And throughout the two centuries that followed, Giovanni Battista Piranesi the person and Piranesi the tormented trope have shared space in the world like a badly executed hologram: never invisible, never quite clear. And so on, until the unfinished stairs and the hopeless Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of the hall.ĭe Quincey never claimed to have seen the etching in question-he was riffing on hearsay from Coleridge-so our compassion is being called into play for an imaginary figure in an imaginary prison in an imaginary etching. But raise your eyes, and behold a second flight of stairs still higher, on which again Piranesi is perceived…. You perceived a staircase and upon this, groping his way upwards, was Piranesi himself…. “Creeping along the sides of the walls,” De Quincey wrote, He wasn’t worried about the real Piranesi, long dead by then he was considering the plight of an etched figure he understood to be Piranesi in one of the artist’s Carceri d’invenzione ( Imaginary Prisons). “Whatever is to become of poor Piranesi,” mused Thomas De Quincey in his 1821 Confessions of an English Opium-Eater.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)